Special Edition Holding Both

A note on hope

My Friends-

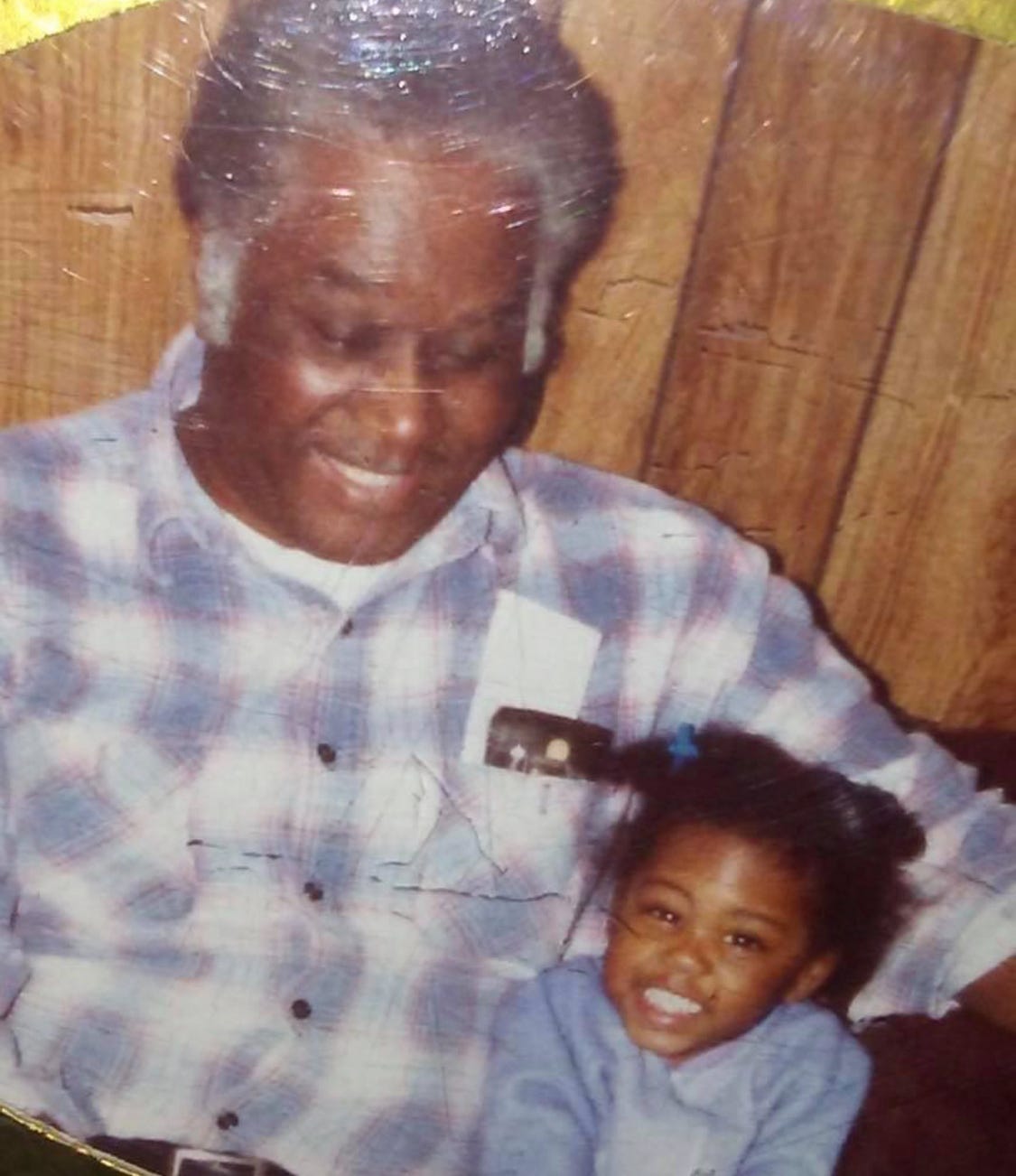

What a week. I am honestly devastated, deeply disturbed, and thoroughly dismayed by the state of our country. I had planned a special Substack collab focused on healing and accessing therapy, but for today, it feels more important to focus on hope. When I feel some kind of way about America, I think of my great-great- grandfather, Bojack Lee, a slave turned landowner. I think of my great-grandfather who turned that land into a business that enabled him, a Black man, to amass a fair amount of property in rural Georgia in the 20s and 30s. And of course, I think of my grandparents and all they overcame to lay the foundation for the life I have today.

To that end, I am sharing my Vogue article from earlier this year. It is OK to grieve the state of our nation, but it is not OK to give up on America. So many people who came before us gave far too much for us to abandon hope now.

I am also going to offer up a suggestion: do something this weekend for someone else. My mother always believed that we can uncover joy by simply being kind and generous to others. Think of Lisa this weekend and buy coffee for the person in line behind you, send someone a funny card, offer to walk a friend’s dog, etc. The action doesn’t matter as much as the intention. In a world full of pain, spreading a little bit of kindness is never a bad idea.

With love and hope,

Marisa

I am a woman obsessed with hope. Not the hope of Hallmark movies, or rainbows, or even the hope that got my former boss, President Obama elected. The hope I am obsessed with is rooted in grief, loss, uncertainty, and the pain of racism. My hope is a violent and powerful thing rooted in the story of my family.

A tale that goes something like this. My grandfather, my Pop Pop, was a hard worker and a leader in the fields where he worked down South in Statesboro, Georgia, where my grandmother’s family originates from as well. He was known as a highly skilled grower and easily transformed the red clay of Georgia into rows of tomato, corn, string beans, and tobacco. He believed in his heart that staying down South was not the right decision, nor the safest one, for his family so he decided to leave Georgia for a new opportunity in Florida, with the ultimate goal being a move North.

The night before they were set to leave Georgia, the white man who owned the fields where my Pop Pop worked and a few of his buddies, showed up at my grandparent’s home with trace chains. The thick metal chains used to attach a horse to a wagon. Their intent plainly was to beat him into submission and force him to stay and work for them. My grandfather met them at his front door, shotgun in hand. The men left, and the next day my grandparents, uncles, and aunt left Georgia.

A few months later, while working in the orange and banana groves in Florida, a nice man from “up North” met my grandfather and offered him a job working in his apple orchards in upstate New York. My grandfather knew this was not just a life-changing, but a lifesaving opportunity for a poor, uneducated, Black man in the South in the 1940s. He readily accepted the offer and began preparations to move his family to New York. My family became a part of the 6 million Black Americans who fled the blatant racial terror and constant violence of the South, for the quiet and subtle racism of the North during The Great Migration.

I think of that night in Georgia often and how terrified my Pop Pop must have been: Wife and children sleeping inside, knowing full well that no policeman was coming to his rescue in rural Georgia. The defense and safety of his family was left to him alone. Everything I have today: my career, my Ivy-league education, a bestselling book, and my physical and psychological safety are all thanks to a shotgun. I am here thanks to the violence of hope. I owe everything to a man (and a woman, cause you better believe my grandmother was behind that decision too!) who felt there was something better for him and his family elsewhere.

He wanted to reach for something more, even if he didn’t even know what it was. They did not know what was waiting for them on the other side of that journey. They left behind family, property, legacy, and everything that was familiar to them. When my grandmother left, she knew she’d never return, so she even signed over land she inherited from her grandfather, a slave named Bojack Lee who somehow became a landowner. They gave up their home and livelihood, and risked their lives, for a future they could not see. That is hope.

So often when we talk about hope, we speak of this ephemeral thing, something that lacks substance and can’t be seen or felt. Something so light and translucent, it cannot be touched or even fully understood. Sometimes, we speak of it as though it is a foolish thing for people who are weak or not grounded in reality. Hope is rarely a thing for grownups with real world problems to address. To me this is simply not true. Hope gave us the Civil Rights Act. Hope gave us marriage equality. Hope gave me my life. Hope, plus hard work, is what we need right now.

Hope is not light or cheerful; it is a disciplined practice and one we need today. Hope requires imagination and dreams. It asks you to choose something better, even when you don’t really know what it looks like. Hope is what has kept Black people not just alive, but consistently moving forward in a country that does not love us back and often attempts to deny our existence. Hope, real hope supported by meaningful action, is the only thing that has ever produced anything truly positive in this world.

Over the next four years, we must reach for hope. A violent hope. A hope that very clearly says, “no, you will not round up my neighbor and deport him and his child.” “No, you will not continue to destroy a planet that is already on fire.” “No, you will not deny the humanity of me, my family, or my friends.” We need a form of hope that is strategic and will do anything to ensure that our collective future is better than our present reality. A hope that doesn’t hide and simply waits out the next four years, but a hope that finds a way through this period of pain and uncertainty rooted in love.

This is a call to arm yourself with hope and support your hope with action. How will you serve and what will you do to produce a better future for all of us and our children? How will you use your time and your talents to save others? The moral arc of the universe does not bend toward justice on its own. Tomorrow grab your own version of a shotgun and get to work.

As a privileged white woman, I can only "think" I imagine what the the great migration meant for you and your family. To think that we as a country are still grappling with the same issues as 100 years ago makes me so sad. I can only hope that we can peacefully address the anger and violence that is an everyday occurance in our lives.